(c) 2013 by Frederick Walton, Historian of the 6th North Carolina State Troops

|

| Sailor's Creek Visitors Center |

My buddy, Richard Otero and I took a Sunday drive to the Sailor’s Creek Battlefield on April 7, 2013. It was one day past the 148th Anniversary of the battle and a good opportunity to see what the battlefield looked like at the time of year the battle was actually fought.

I had been to Sailor’s Creek a couple times before, one being as a participant at the 130th anniversary reenactment in 1995.

| Confederate Troops at the 1995 130th Anniversary Reenactment |

The trip took us about two and a half hours from Wendell, N. C. The weather was sunny and pleasant with highs in the mid and upper 60’s. The drive through rural North Carolina and Virginia was pretty. The blue sky was filled with puffy white clouds and roadside fields tended to be that brilliant, early spring green. I thought we would be treated to more flowering shrubs and trees, but this was the first warm day after a winter that hasn’t wanted to quit, so I guess it was still too early.

|

| Map at Sailor's Creek Visitors Center showing Battle lines |

Our first stop was the visitor’s center at Sailors Creek. This is a relatively new building (I think it opened in 2009) and houses a small, well done museum relating to the battle here. A young lady park ranger, on duty, was extremely pleasant and helpful. I explained that I was looking for information about General John B. Gordon’s Corps and Lewis’s brigade, specifically the 6th North Carolina State Troops. She brought me over to a set of Maps, on display in the exhibit that showed that phase of the battle. These maps are the most detailed I have seen so far, but lacked any detailed narrative to describe the action. She next took me to the tiny gift shop and showed me several books that might provide the narrative. I already own and have read Chris Caulkin’s “The Appomattox Campaign” and I purchased a slim volume of articles by Chris Caulkin entitled “Thirty-Six Hours before Appomattox” and another book entitled “Black Day of the Army, April 6, 1865. The Battles of Sailors creek”, by Greg Evans. I look forward to reading them to see if they will provide the missing details about Lewis’s brigade. She also made me a photocopy of the maps for my reference.

We spent over an hour time leisurely looking at EVERYTHING in the museum. I did not notice any artifacts specifically related to the 6th NCST, but there was an impressive collection of arms, and dug relics representing all branches of the service. One exhibit held a grisly fascination over us. It was an enlarged, very clear, photograph of a dead (Confederate?) soldier, lying in a muddy trench. He had been shot through the head and a massive hole was blown out of the top of his forehead. This really makes you realize the horrors or war, Then, as well as now. This guy, whose name is lost to history, is simply a number in a casualty report, but in reality he was a comrade in arms to his fellow soldiers, somebodies son, perhaps a brother, husband and father, that never returned, changing the lives of dozens of people closely associated with him.

|

| Photo on display at Sailor's Creek Visitors Center |

I asked the ranger if they have a lot of photographs of the battle. As I expected there are not many, but they do have a number of post battle photographs that illustrate what the battlefield looked like shortly after the battle. They are using these to restore the battlefield to its war time appearance, requiring the planting of groves in some areas and the removal of woods in others.

Leaving the visitors center, we turned right, onto the Saylers Creek Road (Va. 617) and proceeded through parts of the battlefield, down to the bridge crossing Sailor’s creek and back up to the high ground where Federal artillery was posted around the Hillman house.

|

| Two Ricks visiting the Hillman House on the Sailor's Creek Battlefield |

The Hillman house was used as a hospital during and after the battle. The owner, Capt. James Hillman, was a captured Confederate officer, imprisoned at Point Lookout or Fort Delaware during this battle. His family was living in the house and retreated to the basement where family lore recalls his wife baking hoecakes for the passing Confederates. Later, when wounded Federal officers where brought into the parlor and the front hall was used as an operating room, blood filled the cracks between the floorboards and leaked through, dripping on the refugees seeking shelter in the basement. The house has been furnished as it may have appeared after the battle when it served as a hospital.

We met Park Ranger R. E. Lee Wilcox who told us about the wounded men who were treated here. About 33 are known to have died here. As we talked about the dead; a wind suddenly shook the open front door and slammed it against its restraints with a loud bang. Gusts whipped around the house. The wind whistling through the closed shutters howled for a few moments then suddenly stopped and all was eerily calm. Richard wondered aloud if the spirits of the dead were making themselves know to us on this anniversary weekend.

|

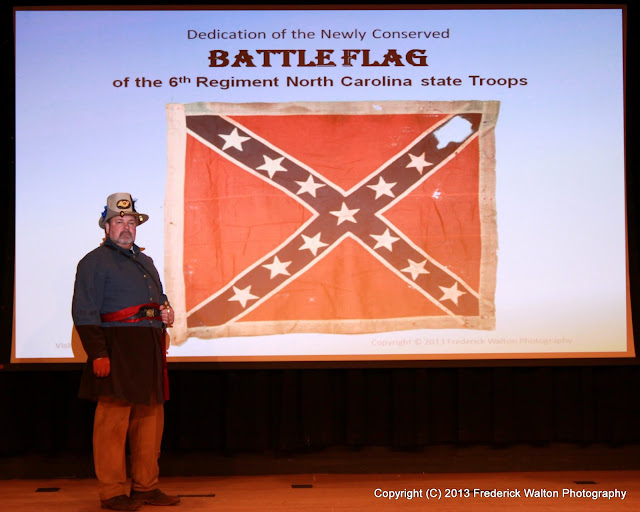

| Author with 6th North Carolina State Troops Battleflag captured at Sailor's Creek |

After touring the house I told Ranger Lee about the Flag ceremony the day before and he seemed interested. I asked him about the position of the 6th NCST at Lockett’s farm. He wasn’t sure of the details but called the owner of the Lockett house, a descendant named Jimmy Garnett. Jimmy invited us to stop by to see him.

Walking back to the parking lot, we noticed a stone wall with a couple of grave stones, peeking over the top, in the middle of the nearby woods. We followed a faint path through the undergrowth and found the late 1850’s graves of some of the Hillman’s children who died as babies. The location was a small knoll overlooking the Hillman house. Down the hill, through the woods our attention was drawn by some overgrown cabins or sheds and then we noticed neat depressions in the ground all around us. The depressions all faced east- west and were in evenly spaced rows and columns. We counted dozens of graves marching off in the distance, presumably soldiers from the battle.

|

| Two Ricks visiting the Lockett house on the Sailor's Creek Battlefield |

We got in the car and continued down Sayler’s creek road to Holt’s Corners and then turned left onto Jamestown Road, which we followed a mile or so through the rolling farmland until it dead-ended on Lockett’s road. We turned left and were now on the road that the Confederate Wagon train and Gordon’s rear guard used as they approached the swollen Sailor’s creek. Jimmy Garnett later told us that a slave boy had been dispatched to warn the approaching wagon train that the double bridge across sailor’s creek was flooded and to divert then down another road. But he doubted the accuracy of this story, because the fork would have led to a gristmill that was closer to the Appomattox river and would have also been flooded too. Either way the wagons were trapped. He repeated another story that mules were shot and thrown in the creek to make it fordable for wagons. He told us that no one is really sure what happened to the wagons, but he personally believed the Yankees looted and burned them. Pointing to his house he said “those aren’t the original shutters, but the ones on the house when I was growing up were supposedly made from wood from the wagons.”

Driving down Lockett’s Road we saw the beautifully restored Lockett House and pulled in to the parking area across from it. After looking over the signage we gazed on the fields where Lewis’s Brigade was posted, according to the maps.

A pickup truck pulled into the pull off and a man got out and came over to us. He introduced himself as Jimmy Garnett, the owner of Lockett House. He was very friendly and informative. Pointing across the field in front of us to the fringe of trees in the far edge, he informed us that was where sailor’s creek flowed. To our left was a stand of trees on a knoll. I asked him if that was wooded during the battle and he said it probably was. He told us that Hank Williams, Jr. had gone relic hunting in those woods and found lots of Minnie balls.

I asked him if the road was the same as it was at the time of the battle. The road is basically the same and the berm on the edge of his lawn above the sunken roadway was formed by wagons passing back and forth throughout the centuries and wearing the road down with ruts.

I asked him what the most unusual thing he found here was. He described the typical things that would be dislodged from the farm fields; Bullets, muskets, bayonets, buttons, “hardly any belt buckles though.” he said.

He thought about it a moment more and then said that years ago a road grader cleaning out ditches near the Hillman house snagged an unknown, buried Federal soldier and dragged him out of the bank. The uniform was faded but you could bend back the collar and see the blue wool. The unfortunate Yankee had a pair of eyeglasses in his breast pocket. The remains were sent to a museum up in West Virginia.

Jimmy told us that they used to have stacks of cannon balls piled on the porch and muskets leaning against the house. His grandmother used to give muskets away to visitors. But during the 1960's centennial, they had so many visitors that his dad took several wagon loads of cannon balls away and buried them in a nearby ravine, because some of them were still live and he was afraid someone would get hurt. Unfortunately Jimmy didn’t give us any muskets or cannon balls.

Speaking of ravines reminded Richard of the disturbing story we heard at the Hillman house. After the battle the Confederates fled. The Federal buried their dead on the field before pursuing them. Following the surrender at Appomattox, the Federals came back for their fallen comrades and took them as they returned north, but the Confederates were left rotting on the battlefield. Meanwhile the Confederate army had disbanded and worn out Confederate soldiers began their long, tiresome journeys to their homes across the south. No one came for the Confederate dead, so the locals gathered their bodies and buried them in a mass grave in a local ravine. Over time the location has been lost. Richard asked Jimmy if he knew anything about it. “I think I know where the ravine is”, he told us, “at least where I’ve been told it is”, he replied without giving away the secret.

|

| Minnie Ball Holes Can still be seen on the Lockett house |

Pointing to a stand of woods opposite his house, he told us that was where the dead from the Lockett house hospital were buried after the battle. All but one had been retrieved by their families for reburial up North. Lower in the woods overlooking the Appomattox River was a huge four story house that belonged to his ancestors. It is inaccessible, but he plans to restore it sometime in the future. He had recently restored the Lockett house. When did some rewiring along the front rooms, he found Minnie balls still lodged in the plaster. Bullet holes are clearly visible across the front of the house. Another visitor asked him why the boards have never been replaced. “Probably because my family was so tight with money”, he replied with a smile. “Those boards are made of heart pine and are so hard; you can hardly drill through them today. There is really no need to replace them for a few holes here and there.”

He invited us to have a closer look and I stuck my finger into several holes at shoulder height, but many more were above my head. General Gordon’s Confederates, across the street, were aiming uphill causing them to shoot high. They must have formed across the road, parallel with the house, rather than along the edge of the road in the field, because the bullet holes seem to be dead on hits, not ragged angular blows.

Not all the deaths came from bullets at the Lockett house. “My grandmother told me that some of the Confederate soldiers were so weak that they died in their sleep, on the lawn, from starvation… she didn’t like to talk about it much because it upset her.” Jimmy said. The house was used as a hospital after the battle and the lawn was covered in wounded and dying soldiers from both armies. Pointing to the front yard he said” There wasn’t as blade of grass that wasn’t red from blood”.

Pointing to a window on the second floor, he said, that’s where our resident ghost lives. He said that his room is next door and he can often hear the rocking chair in that room starting to rock. One time, his son was staying with him and felt a presence in his room. He said “Mr. Ghost, if you are in this room knock on the mantle.” The reply was knock, knock, knock. The ghost is not malevolent, but he is a permanent house guest.

Glancing at my watch I noticed it was half past four. We had talked about dropping by Appomattox on the way home, but it is 45 minutes away so we needed to get going. We bid our farewell to Jimmy and he invited us back to visit him next time we were in town.

We headed down Locketts road past farm fields with that brilliant green of lush vegetation waking up from a long winters nap. I asked Richard to drive slowly, as I hung my head out the window and imagined ragged butternut and gray North Carolinians retreating through these fields, perhaps making a desperate, final stand against a long line of charging Yankee cavalry. Where did they fight? I wondered, where did they lose their flag? We may never know, but I intend to continue my research.

|

| The steep muddy banks of Sailors Creek |

The road rose to crest a hill, and then started a long gradual decline toward the “double” bridge across the creek, our next stop. To our right, the field gently sloped away from the road to the fringe of trees in the distance, marking the course of the creek.

We pulled over right before the bridge. The creek was perhaps 10-15 feet wide. The current flowed from left to right, toward the Appomattox River, out of our sight, and some unknown distance to our right. The current was rapid but the creek bottom glistened in the late afternoon sun. In spots it was merely inches deep, and even in the deeper water it probably wouldn’t have been past our knees, but neither of us felt like testing this notion. The steep vertical banks told a different story however. At some spots it was, probably, a five or six foot drop to the stream. I imagine that at some time, fairly recently, a raging current cascaded through this ravine cutting the soft Virginia clay into a steep sided, miniature grand canyon. This would make a great defensive breastwork trench, but if I was running for my life from a cavalry charge, I would not like to stumble into this abyss.

I picked my way down the slippery, crumbling bank to take some photos. I could have easily picked my way across here with little trouble. I thought about marching in formation during civil war reenactments or tacticals. We march shoulder to shoulder, or, sometimes when broken apart by woods, in a looser disorganized line formation, but in either case, there is little opportunity to pick your spot. You get herded to the spot in front of you, and if that is a 6 foot drop…oh well! This would not be an impassable obstacle to infantry, at least on this day, but if the bridge was out, like Jimmy said, and the creek was overflowing its banks, the ground a mire of mud from troops and horses, it would be tough getting across, especially when being closely pursued by the enemy.

An older, overgrown track paralleled the modern road bed, leading to a twisted iron bridge almost silted over. It looks like the creek bed had shifted course slightly were the two branches of the sailors creeks merged. Jimmy had mentioned this to us. Next to the pull off lay the rotting carcasses of a field canon carriage, the broken wheels where chained to trees to prevent their removal. I suspect that they date to the centennial or perhaps the 125th anniversary time period, but it would be a shame if this was an original carriage abandoned to rot due to funding cuts.

|

| Part of the Sailors Creek Battlefield |

We walked into the long, low, field along the banks of the creek. Looking away from the creek ,the plain in front of us was separated from the sloping hill by a fence line of trees. Somewhere on this plain the Confederate made a stand, with their backs to the creek, at least according to the maps. I could imagine the familiar site of my reenacted friends in the Carolina Legion stretched out to my left, backs to the creek, ready to resist an enemy charge.

The sun had fallen behind the hill rising up the opposite side of the creek. This is ground that Gordon’s corps climbed late in the day of April 6, 1865 after an afternoon of desperate fighting along sailors creek. We returned to our car and drove up the hill and onward toward Rice’s station and the high bridge. We made a stop at Rice’s Station to read the Lee’s Retreat sign board before heading to the High bridge. We got off the track, ending up in Farmville. The sun was rapidly making it’s decent and we had more than a two hour drive to get home. We called off the search and decided to come back to the high bridge and Appomattox on another visit.

Richard and I had spent the day walking the ground where the 6th NCST fought 148 years and one day ago. I now have a better feel for the terrain they fought on, although I would like a better narrative describing the events of that part of the battle. At least one account of the battle described the Federal soldiers admiring the brilliant red sunset that evening, only to learn later that it was the glare from the burning wagons that was illuminating the twilight.

As we headed home, the sun was starting to fall, casting long sgadows of the spring green farm fileds and wood lots whizzing by. The western vista suddenly opened up and the sun was an enormous red ball balancing on the horizon. Looking closely at the beautiful end of this day’s adventure, I thought once again about the soldiers. There were no wagons burning tonight, just the memory of a great battle that was fought here.